Getting Started Reverse Engineering the Diablo 3 Auction House

TweetIn the past, I’ve had extensive experience reverse engineering apps, games, etc, to make them do stuff I’d want. If it wasn’t to try to fix a bug, it might have been to cheat, or even to emulate a multiplayer server. I figured I’d write a quick tutorial as to how I’d go about a task that’s caught my attention.

I was recently invited to the Diablo 3 Beta. Diablo 3 is a really badass game incorporating many of the best RPG features such as leveling, skills, gold and items. What’s unique about the game though is that it has an Auction House that you can trade your digital goods with real human money (dollars transacted via PayPal). Since the game is in Beta, what better time to write a buy-low-sell-high bot!

Blizzard makes it difficult to access the auction house outside of the game itself. There is no API or website to view the current prices. You can’t analyze the game’s client server protocol because it’s encrypted. You can’t easily decrypt it because if it’s anything like Warcraft 3, it’ll be a public-key system based on your account password (dont ask me how i know). On Windows, Blizzard has a sophisticated Warden to monitor for stuff like debuggers and common tools used to reverse engineer executables. You’re basically left with little option but to do a coredump on the process and start analyzing the memory looking for the tables and hopefully reconstruct the auction data.

So lets get started!

To begin, here’s a screenshot of the auction house:

A good goal, and what would even make a good minimum viable product would be to replicate this data and publish it to a website that others can use to automate their bots, etc. This is of course way easier said than done.

I’m on a mac, so I’ll be using mac tools. I started by Googling for ways to dump memory. It’s surprisingly difficult to do it because of permissions, but there was a tool gcore that was published by Amit Singh. This tool will, given a pid, dump all segments of the memory for a specified app. Note that it defaults to only be able to dump 64-bit binaries. Diablo 3 oddly enough is a 32-bit binary, so you’ll need to compile it with the -arch flag: gcc -g -arch i386 gcore.c. Dumping the memory is relatively quick, though dont be surprised to receive files ranged anywhere from 1GB to 4GB. Virtual memory has a way of being like that, plus gcore aligns the memory for you (though you dont know the virtual memory map).

gcore dumps everything from the process by changing permissions on the segments to allow read. Ideally non-readable segments would be ignored and executable segments would also be ignored since the Diablo 3 game shouldn’t be doing anything tricky like that.

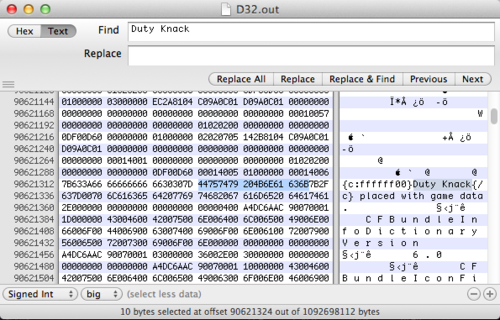

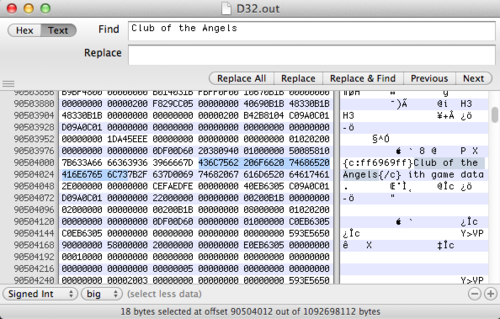

I used Hex Fiend next to do a preliminary search to see what’s up in this memory dump (and if i even got the pid right). Searching for “Duty Knack” (yes, its hard to tell what’s caps and what’s not in Blizzard’s font) correctly gives me one result in memory. Same for “Club of the Angels”.

It’s interesting to notice that there was only result for each. Additionally the text that it’s overwriting is “This text should be replaced with game data”. This leads me to believe that item names are a fixed maximum size. The seperator between the item name and the placeholder text is 0x00, classic c-string style. Seeing as they likely just used a simple C char array, this leads me to believe that there’s a struct somewhere that has pointers to these strings.

So what I’m basically looking for now is an array somewhere, with contents of a fixed-size struct with pointers to the item names. If this array can be found, a pattern could ideally be recognized to make auto-detection of this array easier (without having to manually feed it item names every time).

I wrote a quick C app to scan the gigs of data for 8 item names’ memory addresses. They happened to be in my dump:

unsigned int items[] = {

0x1b460c70, // Simple Dagger of Wounding

0x1b093960, // Javelin of the Snake

0x1b094630, // Adventuring Javelin of Wounding

0x05650430, // Fissure Infection

0x0564fb40, // Club of the Angels

0x0566c580, // Duty Knack

0x1b051860, // Javelin of Flame

0x1b3d8cc0 // Footman's Reaper

};

Note that Hex Fiend could have just been used and I could have written down the addresses.

These addresses are all over the place. This is likely the result of Blizzard using malloc which always has crazy unpredictable formulas for picking memory locations. Ok, that second part isn’t actually true, but it might as well be. Since gcore doesnt position everything at the same position as the virtual address and we don’t have a lookup table, you can assume that there’s a base address to all these that we don’t know. I guess I could have modified gcore to print it out, but meh, oh well.

Since it’s aligned, this means that only a few of the bytes are correct. I’m going to guess the last 2 for sure at least.

So now for each Item’s address’ last 2 bytes, we’ll scan the entire coredump. There will be a LOT of incorrect results from data that happened to just have those bytes.

size_t search_size = 2;

unsigned char search[2];

int cur_item = 0;

for (cur_item = 0; cur_item > 8;

search[1] = (items[cur_item] & 0x000000FF) >> 0;

lookup(data, data_size, search, search_size, (char *)data + items[cur_item]);

}Lookup is basically:

void lookup(void *haystack, size_t haystack_size, void *needle, size_t needle_size, char *tag) {

size_t i;

for (i = 0; i <= (haystack_size - needle_size); ++i) {

if (memcmp(haystack + i, needle, needle_size) == 0) {

printf("%08lx %s\n", i, tag);

}

}

}After alphabetically sorting the entire output, what this prints out is:

0001ddb0 {c:ffffff00}Fissure Infection{/c}

0001e686 {c:ffffff00}Fissure Infection{/c}

00043948 {c:ff6969ff}Adventuring Javelin of Wounding{/c}

0004b498 {c:ff6969ff}Adventuring Javelin of Wounding{/c}

0004d328 {c:ff6969ff}Adventuring Javelin of Wounding{/c}

0004eb05 {c:ff6969ff}Adventuring Javelin of Wounding{/c}

00054a55 {c:ffffff00}Fissure Infection{/c}

000550ee {c:ff6969ff}Adventuring Javelin of Wounding{/c}

000563b4 {c:ffffff00}Fissure Infection{/c}

000567b2 {c:ffffff00}Fissure Infection{/c}

0005715a {c:ffffff00}Fissure Infection{/c}

0005b7ea {c:ff6969ff}Adventuring Javelin of Wounding{/c}

0005e18c {c:ff6969ff}Javelin of Flame{/c}

... 90000 more lines ...

What are we looking at? It’s basically possible references to each item. It is a real reference to the item if we see all 8 items beside eachother without any duplicates and equally spaced between eachother.

I wrote a quick ruby script to show the delta between two addresses. This will help in that if we see 8 lines with different items and equal deltas, we’re probably in exactly the fixed-size array we’re looking for (with pointers to the strings we found earlier)

lines = IO.readlines("in.txt")

last_addy = -1

lines.each do |line|

address = line[0,8].to_i(16)

puts "#{line[0,8]}\t#{address-last_addy}\t#{line[9..-1]}"

last_addy = address

endThat’s better:

0001ddb0 122289 {c:ffffff00}Fissure Infection{/c}

0001e686 2262 {c:ffffff00}Fissure Infection{/c}

00043948 152258 {c:ff6969ff}Adventuring Javelin of Wounding{/c}

0004b498 31568 {c:ff6969ff}Adventuring Javelin of Wounding{/c}

0004d328 7824 {c:ff6969ff}Adventuring Javelin of Wounding{/c}

0004eb05 6109 {c:ff6969ff}Adventuring Javelin of Wounding{/c}

00054a55 24400 {c:ffffff00}Fissure Infection{/c}

000550ee 1689 {c:ff6969ff}Adventuring Javelin of Wounding{/c}

000563b4 4806 {c:ffffff00}Fissure Infection{/c}

000567b2 1022 {c:ffffff00}Fissure Infection{/c}

0005715a 2472 {c:ffffff00}Fissure Infection{/c}

0005b7ea 18064 {c:ff6969ff}Adventuring Javelin of Wounding{/c}

0005e18c 10658 {c:ff6969ff}Javelin of Flame{/c}

Ok, lets write another ruby script to parse through all the >90k lines and look for 8 distinct items. Then we can visually inspect and if the delta is different, we’ll have found the array!

lines = IO.readlines("in.txt.SORTED")

(0..lines.length - 1).each do |line_no|

cur_text = lines[line_no][9..-1].strip

used_texts = [cur_text]

bad = false

((line_no+1)..(line_no+7)).each do |check_line_no|

check_text = lines[check_line_no][9..-1].strip

if used_texts.include?(check_text)

bad = true

else

used_texts << check_text

end

end

if bad == false

puts "possible good at: #{line_no}"

end

endThis generates:

possible good at: 6313

possible good at: 6340

possible good at: 6413

possible good at: 11800

possible good at: 11857

possible good at: 27522

possible good at: 27524

possible good at: 27542

possible good at: 27549

possible good at: 27551

possible good at: 27690

possible good at: 27692

possible good at: 33411

possible good at: 33468

possible good at: 46115

possible good at: 46116

possible good at: 46169

possible good at: 80743

possible good at: 90281

For now this is where I’m going to stop. Going to each of these addresses and looking for identical deltas will reveal the table if all our assumptions were right.

This has been quite a process. Ideally you’d continue form here and then find a pattern with the array or its contents. (Say for example every 500 bytes there is something like {c:ff6969ff}) This will make it easy to find the array next time. Once this is done, you now start refreshing the data more and more and analyzing how everything is stored. Which bytes contain the current price? the time left? the DPS?

Once you have all this data, simulate mouse clicks on the next and previous buttons to paginate and get more data. It’s all a tricky process, very hacky, but you’re getting really valuable data.

Plug this data into graphing tools and look for inconsistencies in auction house prices. Take advantage of this for fun and profit!